The ability to generalise well is one of the primary desiderata of models for natural language processing, yet how “good generalisation” should be defined and what it entails in practice is not well understood. To be able to better talk about generalisation research in NLP, and identify what is needed to move towards a more sound and exhaustive approach to test generalisation, we present an axes-based taxonomy along which research can be categorised. Below the infographic, we describe the meaning of the different axes. If you are interested in exploring the results of our taxonomy-based review of over 400 generalisation research papers, check our generalisation map exploration page, or search through the references. For a more detailed description of the taxonomy and the survey, have a look at our paper, and for a comprehensive audiovisual summary watch the video produced in collaboration with SciTube. You can describe your own experiments with our taxonomy by including GenBench evaluation cards in your research papers.

The taxonomy axes

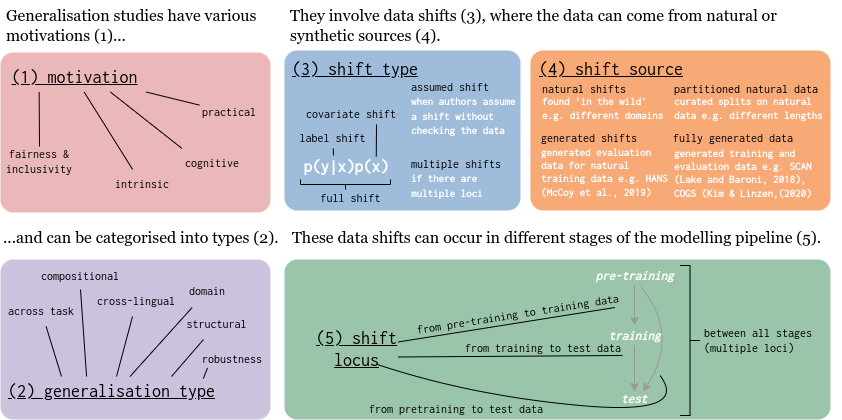

The generalisation taxonomy contains five different (nominal) axes along which generalisation research can differ: their main motivation, the type of generalisation they aim to solve, the type of data shift they are considering, the source by which the data shift was obtained, and the locus of the shift.

Motivation

The motivation axis illustrates what kind of motivations are used in a generalisation test. We distinguish four different types of motivations: the practical motivation, which characterises studies that evaluate generalisation to understand in which scenarios models can be applied, or with the concrete aim to improve them; the cognitive motivation, which includes papers that study generalisation from a cognitive angle, or because they would like to learn more about humans; the intrinsic motivation, which instead considers studies that look at generalisation purely from an intrinsic perspective, to better understand what kind of solutions a model implements or what factors impact that; and the fairness and inclusivity motivation, which is used for studies that are motivated by the idea that models should generalise fairly, for instance to different sub-demographics or low-resource languages.

Generalisation type

The second axis describes the type of generalisation a study looks at. On this axis, we consider five different types: compositional generalisation, which considers whether models can compositionally assign meanings to new inputs (or broader, compositionally map new inputs to outputs); structural generalisation, which includes studies that consider whether models can generalise to correct syntactic or morphological structures – without considering whether those structures can also be correctly interpreted; generalisation across tasks and generalisation across languages, encompassing studies that consider whether a single model can generalise from one task or language to another, respectively; generalisation across domain, which considers whether models can generalise from one domain to another, considering a broad definition of ‘domain’; and robustness generalisation which considers how robustly models generalise when faced with different input distributions representing the same task.

Data shift type

The third axis is statistically inspired and describes what data shift is considered in the generalisation test. We consider three well-knows shifts from the literature: covariate shifts – shifts in the input distribution only; label shifts – shifts in the conditional probability of the output given the input; and full shift, which describes a shift in both input and conditional output distribution at the same time. Because shifts can occur at multiple stages in the modelling pipeline – as described in the next section – we furthermore include the category double shift, used for cases where the experimental design investigates multiple shifts at the same time. Lastly, we observed that several studies in the literature claim to investigate generalisation, but do not actually check the relationship between the different data distributions involved in their experiments. For those kinds of studies, we – hopefully temporarily – include the label assumed shift on our data shift type axis.

Shift source

On the fourth axis of our taxonomy, we consider what data source is used in the experiment. The source of the data shift determines how much control the experimenter has over the training and testing data and, consequently, what kind of conclusions can be drawn from an experiment. We consider four different scenarios. The first possibility is the scenario in which the train and test corpora mark natural shifts: they are naturally different corpora, that are not systematically adjusted in any way. In the second scenario, instead, all data involved is natural, but the data is split along unnatural dimensions, we refer to this source with the term natural data splits. Scenario three – generated shifts encompasses the case in which the training corpus is a fully natural corpus, but the test corpus is (adversarially) generated – or the other way around; the fourth and last option is used for studies that use data that is fully generated, for instance using templates or a grammar.

Shift locus

The last axis of our taxonomy describes where in the modelling pipeline generalisation is considered, or, in other words, what is the locus of the shift in the experiment. Given the three broad stages in the contemporary modelling pipeline – pretraining, training and testing – we mark five different loci: the train-test locus, used for experiments that focus on the classical case where a model is trained on one distribution and tested on another; the finetune train-test locus, indicating experiments where a pretrained model is finetuned on some data and then tested on a dataset that is o.o.d. w.r.t. the finetuning data; the pretrain-train locus, which includes studies that consider shifts between pretraining and training data, but not between the finetuning and testing data; the pretrain-test locus, which we use to indicate papers that use a pretrained model that is not further finetuned but tested directly; and, lastly, multiple loci, which we use for studies where there are shifts between all stages of the modelling pipeline, and those are also all subject in the generalisation experiment.

Contribute to the review

We would love to hear what you think about the taxonomy and include more papers in our review. Did you also work on generalisation, and would you like to have your work included in our review and generalisation database? See the instructions on the contributions page.